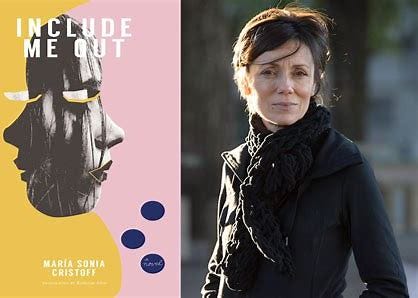

I’ve been thinking a lot about resistance lately and noticing how persistent a theme it is in the books by women I’ve been reading, not only resistance writ large, but small acts, everyday acts. And as it happens, this is also the preoccupation of the Argentine author Maria Sonia Cristoff.

Interweaving fiction and non-fiction, Include Me Out is a darkly comedic novella (I love this short form—they’re little gems). The main character is Mara—a formerly successful simultaneous translator. Fed up with repeating the empty words of the rich and powerful, she dramatically quits mid-engagement. Constant speech is the role of an interpreter. So, she decides to dedicate herself to silence and takes a job as a museum guard in a small Argentine town. She revels in the silence but is also challenged in it by the people she connects with.

The author thinks of Mara as her alter-ego. Cristoff is a translator as well as a writer and academic. In her thirties, Cristoff ran away from her job as a high school teacher to the south of Argentina where she grew up, summers at her Bulgarian grandfather’s farm and the rest of the year in a small, industrial town. She loathes a system where so much of what is done for work sucks out human vitality. Those who are “against the grain of the situation” (a favourite phrase of hers) are always looking for ways to set up an escape or some sort of sabotage, she believes.

In the novella, Mara, her alter-ego first chooses silence and stillness as resistance. When this is threatened, “she fully understands those women who sweep the sidewalks in front of their houses every Sunday…There’s fury, anger, rage, furiously angry rage behind it…As she sweeps she touches those [museum] pieces with her broom, raising dust, disobeying as she sweeps…” (Include Me Out, p 42).

Is Mara slightly unhinged? Yes. The author sees that, too, as necessary for resistance. So, as her first act of sedition, Mara decides to sabotage emblems of revered and fossilized tradition.

Argentina has a long history of both oppression and resistance. From the beginning, it was a society that rewarded militancy rather than pioneering. And that has persisted.

When the Spanish colonists rebelled against Spain and obtained independence, local military leaders were granted huge tracts of land for ranching. These founding families—essentially cattle barons—became the elite of Argentina and have dominated it ever since. (Beef is still the basis of the economy.) They hobnobbed with British aristocracy, imitating their manners, dress and interests (gotta love that polo!). To this day, the elite wish that they were rich Europeans instead of rich Argentinians.

The Spanish were involved in the slave trade though on a small scale (however small it was, too large for those enslaved), since raising cattle—its main source of income—isn’t labour intensive.

But soon Black inhabitants formed a third of the population. Race was perceived differently by white Argentinians than by white Americans. It isn’t that Argentine racism was less vile, but while white American paranoia about mixing led to the one-drop rule, in Argentina mixing was seen as the solution to blackness.

Intermarriage was encouraged and so was immigration from Europe to “lighten” the population. There wasn’t any reason for the elite to be paranoid because all these people were far beneath them. Immigrants—more than half Italian, Germans being the next largest group—were invited to be subservient labourers under their thumb. There was no Argentine dream. They were never intended to rise any higher, certainly not share in the land and wealth of the nation.

From the nonfiction “Notebook” in Include Me Out (p 17):

The museum of Luján, today Udaondo, and its initial role as a shield against the cosmopolitan version of the nation…On that shield: the gaucho and the Indian…An embalmed Mataco Indian…The wax gaucho and the embalmed horse…Exhume the dead, exhume Indians and gauchos, like so many crucifixes to hold up against the threat of the poor immigrants disembarking from the ships.

What about the Indigenous? Before colonization, a number of Indigenous groups lived in the area. Just prior to the arrival of the Spanish, their main concern was the incursion of Incas. But the Spanish wiped out all these groups, first in the fertile northern part of Argentina. After independence from Spain, the last massacre of Indigenous people occurred in the early twentieth century and resulted in the annexation of Patagonia, the grasslands of the south.

Antisemitism was also alive and well in Argentina. With its authoritarian elite and its immigrants from Axis countries, there was a lot of sympathy for fascism and the Hitler regime. During World War II, Argentina affected a sort of neutrality. But post-war, during one of its democratic interludes, the president, Juan Perón, facilitated Nazi immigration to Argentina.

This is a country that not only has huge inequity—the elites still dominate and half the people live in poverty—but has also often been under the rule of repressive military dictatorships. Until the mid 1980s, there was one coup after another. Yet what I find really interesting are the widely different forms women’s resistance in Argentina has taken—interesting and inspiring.

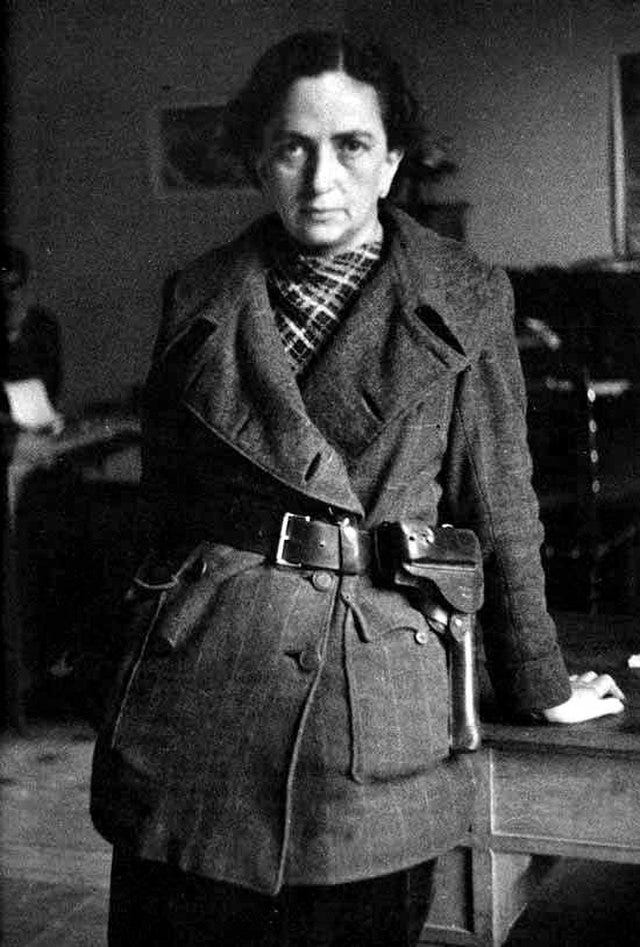

For example, take Mika Feldman de Etchebéhère, a young Jewish-Argentine woman, whose parents had fled persecution in Eastern Europe. During the Spanish civil war in the 1930s between fascists and anti-fascists, she went over to Spain to lead a militia against the fascists.

Sadly, the fascists won, and Spain lived under a dictatorship for the next forty years, right up to the mid 1970s. (Something I’ve been realizing with my Reading Women Project is how recently many countries in the world have become democracies).

But the mid 70s is just when Argentina’s worst dictatorship came to power (supported by the US as a bulwark against communism). This is the regime, led by General Jorge Rafael Videla that conducted “The Dirty War.”

That was the military dictatorship’s term for using army, security forces, and death squads to hunt down political dissidents. The military estimated that they’d secretly abducted and murdered about 22,000 people. It’s believed to be quite an underestimate.

Most of those grabbed were young people, whether activists or simply university students suspected of whispering about freedom, and writers who spoke their minds. They were confined, tortured, and killed. Jewish students were ten times more likely to be among them. They were subjected to particular abuse accompanied by Nazi slogans. The LGBTQIA+ community was targeted, too.

(And, yet, today, Argentina has laws that provide full protection for transgender rights. It was the first country in South America to legalize same-sex marriage. Change is possible.)

For eight years, The Dirty War was conducted covertly—people simply vanished. They were called “the disappeared,” and their mothers were left wandering from one authority to another, looking for help to find their children.

Eventually, they started running into each other at police stations or other places of enquiry, and came to realize it wasn’t just their own child who was missing.

The mothers of the disappeared held their first rally at the end of April in 1977. They wore white kerchiefs—because easily visible—embroidered with the names of their missing children. It was illegal to gather in groups of three or more; it was illegal to stand around. So, they walked two by two around and around the Plaza de Mayo in front of the presidential palace. They continued to rally there every week for the next thirty years, seeking answers and justice. Although the dictatorship ended in the mid 1980s after instigating the disastrous Falkland War (I’m old enough to remember how bizarre it was to see the British naval fleet sail to war like in days of old), initially there were no repercussions for The Dirty War and no convictions until the 2000s.

Resistance can be with arms, like Mika Feldman de Etchebéhère, it can be public solidarity and protest, like the mothers of the disappeared, but it also occurs in small daily acts. In interviews, Cristoff refers to the ideas of everyday resistance expressed by Michel de Certeau and James C. Scott.

From his work in Southeast Asia, Scott—a political scientist and anthropologist—observed that the weapons of the weak are small, covert acts, like farting while bowing to the lord of the land, or nicking something from a bad workplace. They may not seem like much, but they boost a sense of self and provide some sort of gain. And however small, they add up, creating a permanent layer of resistance in the struggle against domination.

The attitude that only mass movements make a difference is represented in the novella by a character named Helen, an old leftie, someone that Mara trusts and confides in. Though Helen doesn’t disapprove of Mara’s intended sabotage as asocial or illegal, she is disapproving and dismisses it as insignificant because it’s just the personal action taken by an individual. But Scott—and Cristoff—believe in everyday, individual resistance.

[H]er commitment to the no, or at least to the no to everything she knows so far because in Mara not everything is renunciation, there is not in her a pure absolute no, but rather a commitment to the search for alternative ways, for other possible ways of life, and that search is undoubtedly a political gesture, and a gesture of anarchist trace if it is not a matter of confronting it gregariously but, as Mara chooses, alone.

- Maria Sonia Cristoff (link to interview below)

Include Me Out is a weird little book, and I mean that in the best way. At first, I had no idea what was going on, but I was drawn in by the wry humour, the nonfiction passages in the notebook sections, and Mara’s observations. For example, this (p 51), one of many on different functions of silence:

Silence is prudent when we know how to not speak in an opportune way, according to the moment and the place in which we find ourselves in the company of others, and according to the consideration we must show to persons with whom we are forced to deal and live.

I think that women, in particular, cultivate resistance because, whatever the circumstances faced within a society, women face that plus patriarchal oppression—whether light or heavy—and its accompanying misogyny. In Spanish, appropriately, the word for resilience, resiliencia, is feminine. May we not always face this double burden. And in the meantime, may our resilience carry us through.

Sources:

Video interview with Maria Sonia (Use CC plus settings for auto translate)

Interview with Maria Sonia Cristoff (use auto translate in browser)

Interview with Maria Cristoff (as above for translation)

History of Argentine literature, 90% reviewed are dudes (because you know)

Lilian I am absolutely loving these posts - they're brilliant. Pure class. Thank you for sharing them with us; I learn so much.