Although this is only the third country in my reading women project, patterns are already emerging. For one: as go the women, so goes the country.

There isn’t a single Angolan woman novelist listed in Wikipedia, and only eight poets. None of them were born after 1960. By comparison, Canada—with the same population—has had some 900 women novelists, and 600 poets.

Maybe Wikipedia is missing something, I thought, so I did a search. Nothing else came up. Then I did a search in Portuguese, using Google Translate (a trick I learned while doing research on women fighter pilots in WW2 for Girl at the Edge of Sky). I found one more poet from the older generation—but more excitingly—I discovered that there are young poets participating in spoken word contests.

And this is despite the barriers that women face in this conservative, Catholic, war-wrecked country. Teenage pregnancy is high in Angola, marriage young, domestic violence rampant. Compulsory education ends at age eleven, and nearly 40% of women are illiterate because they can’t afford to continue their education.

On paper, Angola ought to be thriving. It has oil, minerals, vast arable land, a good climate for crops, beautiful landscape.

But for 400 years, the economy of various African kingdoms in what is now Angola was based on the slave trade initiated by the Portugese. Many men were lost to it—sent to Brazilian mines and plantations. African kings and nobles were often at war with each other and with the Portuguese who were always trying to push further inland. And then, after slavery was finally abolished in the 19th century, and European powers carved up Africa for themselves, all of Angola was under the domination of Portugal. This didn’t end until the mid 1970s, after a thirteen year war to gain independence.

There are no books by Angolan women translated into English, but I found a few poems online. This one speaks to the war.

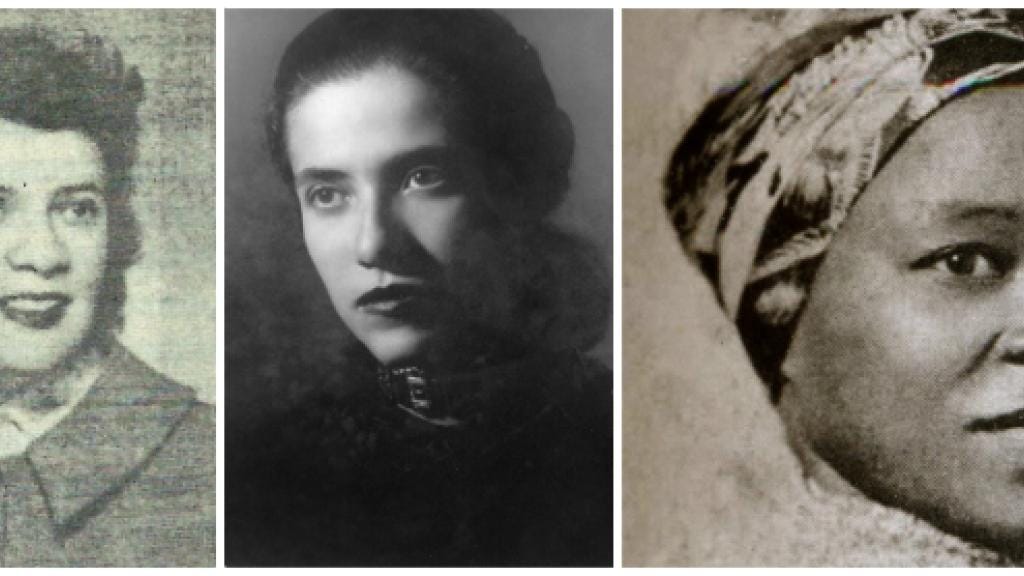

From “Asking” by Deolinda Rodrigues (written in the 1960s, translated by Chris Daniels):

Cold-blooded murderer,

commie spy,

woman playing at politics,

whore.

They’re calling me all these things

and here I am asking when this nightmare will end,

asking

each time their feet go by,

the military jeep growls,

the bugle sounds reveille.

There’s a new guard at my door.

Deolina Rodrigues was born in 1939. Her parents were both teachers. As a teenager, she moved to the capital and lived with her aunt and cousin, the poet Agostinho Neto, who became the first president of Angola and married a Portuguese-Angolan who was also a poet.

Rodrigues fought in the War of Independence, which only ended because of a coup that put a Portuguese president in power who said, meh, we don’t need colonies anymore. As was the case in Algeria’s War of Independence, different factions united for the duration of the war. These factions not only represented different political ideologies, but also consisted of different ethnic groups.

Sadly, Rodrigues was captured and executed during the war, but not by Portuguese forces. No—it was another Angolan faction that ambushed and imprisoned her and her fellow soldiers.

After Angolan independence, these factions fought a bitter civil war that lasted twenty-six years. They were backed by opposing world powers—Russia and US primarily (China was involved initially, too)—who supplied arms to opposing parties. The payoff—if their party won—would be influence. (This type of proxy war persists until today with Asian countries like China and Pakistan involved, too, all over the world).

During the Angolan civil war, which ended only in 2002, millions of landmines were strewn across the country, ruining the lovely fertile land. Farmers fled to the cities where there was no work. As a result, now food has to be imported.

The capital, Luanda, is currently an expensive city of extremes: a few wealthy enclaves surrounded by crime-ridden slums. The (often white) professionals from overseas who dominate the oil industry live in barricaded enclaves, and if they venture out, it’s with an armed driver. Money from oil is funnelled into the corrupt hands of government and their cronies. Dissent is crushed by the government, run by the Russian-backed MPLA, the party that Deolinda Rodriges fought with, the party that won the civil war.

Far and Away by Alda Lara:

Don't cry Mom... Do as I do, smile!

It transforms the elegies of a moment

into songs of hope and incitement.

Have faith in the days I promised you.And believe me, I am always close to you,

when on moonlit nights, the wind,

whispers its lament to the coconut trees,

composing verses that I have never written...I am with you in the days of brazier,

at sea... on the old bridge,... in the Sombrero,

in all that I loved and wanted for myself...Don't cry, mom... The time is for moving forward...

We walk right, hand in hand,

and we will reach the end one day...

Alda Lara, Portuguese-Angolan, was born in 1930 and came from a wealthy family. Like her, most of the women Angolan writers from older generations come from privileged backgrounds, many of them white or mixed race. On the other hand, the young generation of women poets, those entering spoken word contests and posting on YouTube, are mainly Black Angolans, who form 92% of the population.

There are pockets of hope for women—and how women go, so does the country. As of last year, more than a third of seats in parliament were held by women. Half the landmines have been cleared. Millions still remain, and forty percent of the local people involved in clearing them, which is well-paid work, are women. Traditional midwives are being educated in the treatment of diseases like HIV so that they can help rural women, who trust them, get access.

There are several women’s organizations in Angola, all doing good work. However, they’re careful not to push, presenting themselves as government partners, not critics, because the ruling party, the MPLA, doesn’t take kindly to critics, using violent repression to shut them up. In response, a recently formed (2017) women’s organization, Ondjango Feminista, aims to broaden the reach of feminism through activism and education.

Angola has an old tradition of women leaders like Queen Mwongo of Matamba, which had a culture of female leadership. Her kingdom was conquered by Queen Nzinga of Ndonga—who had to fight against her nobles’ discomfort with a woman in power in the early to mid 1600s. (The name of the country, Angola, comes from her people’s word for ruler, Ngola.)

Queen Nzinga was the daughter of a king and his favourite concubine. She was a savvy, wily politician and tactician in diplomacy and in battle, making alliances with Europeans and other African kings. Breaking those alliances when her sovereignty was threatened, she retreated and advanced over the years, surviving into her 80s in an era when disposing of rulers and their offspring was commonplace (a practice that she wasn’t immune to, either).

In the spirit of her strength, her present day daughters carry on. I’ll end with an excerpt from a powerful spoken word poem by Joice Zau, who won the 2021 Lusophone (Portuguese) Female Spoken Poetry Championship in Brazil.

Extract from “Between Peace and Love, I Prefer Love,” by Joice Zau:

I absolutely hate peace

Screw it, morals and good customs, the laws of physics that govern nature in time and space, I hate peace and I'm not of peace

Peace doesn't mean anything to me, peace doesn't represent me

Peace, a rag to a stained social fabric, peace is feigned

Peace, pretends that freedom springs, while it makes us products on a conveyor belt and controls us through antennas

Peace, wreaks havoc in winter, comes with a smile that opens like a flower in spring and corrupts our cries for justice

Watch her speak the poem here—she is not holding back, either in words or speech. (For English, click on cc for captions, click on settings and select auto translate.)

And lastly, a map: From Algeria to Angola. I am geographically challenged and am always amazed by a) the fact that the world is round and everything meets and b) countries are never where I imagine. And omg the Sahara is huge! I never realized.

This was fascinating to read, and made me realise that I know so very little about African writers per se, not just those in Angola! It's wonderful to read this poetry and so very good to have you collect it together here, along with such informative commentary.

Thank you for writing this piece. I'd read (recently) that publishers do not often publish African writers because they (publishers) claim that there's no market for literature in African, and I believe that prejudice is especially true of subsaharan Africa, but excludes, I presume, a few African nations such as Egypt, South Africa, Morocco.

Thank you for putting the time into researching and finding the poets on YouTube and elsewhere, and highlighting their work.